Melbourne v Collingwood – Rivalry in red, blue, black and white.

Nigel Dawe

According to Western folklore, the word ‘rival’ stems from the old Roman word ‘rivus’ (meaning stream, river, or water source) and by extension ‘rivalis’ meant “one who uses the same stream as another [for sustenance and survival].” In the same vein, some of the oldest definitions in English for the word and notion ‘rival’, denote it as “having the same pretensions or claims, holding the position of rivals… To stand in or enter into competition with another; to strive to equal or emulate.”

Which could not more encapsulate what the Collingwood Football Club has meant to the Melbourne Football Club since having first met ‘in earnest’ on the 19th of June in round 6 of season 1897. That day Melbourne came away 7-point victors, but that initial success was far from how things would pan out across the years.

As such, our record against the Magpies is the worst of any team we have played. In the 246 official encounters against Collingwood, the MFC have left the ground only 85 times with a ‘W’ in their win/loss column. But fascinatingly, and this is where the necessary friction and deep factional divides are required for a rivalry to take flame; Melbourne have the best record against Collingwood when it matters most – that being in the beautiful month of September.

Of the 23 times we’ve played Collingwood in a final, the Demons have won on 16 occasions and drawn once. That draw (in 1928, the first in a finals match, let alone in a Preliminary Final) signaled, albeit demarcated a point (and pardon the pun) of no return in the rift that still healthily exists between the two clubs.

That day, which was defined by scribes as being gale force to downright dangerous (with scraps of paper and debris of all kinds swirling about and above the MCG) ended in a draw that should’ve resulted in a one-point win to Melbourne. Incredibly, a point was awarded to Collingwood’s Bruce Andrew after the 3-quarter time siren. In his later years, Andrew embellished his version of events with the stipulation that the point was never awarded, but that’s the nature of research-based evidence, it does eventually catch up to what is said with regards to what actually takes place.

In itself it ‘wasn’t much’, but if that solitary point hadn’t been awarded in 1928, then Collingwood’s famous ‘Machine’ that won a record setting 4-premierships in row, from 1927 to 1930 would never have occurred. The following week, history shows that Collingwood won by 4-points, going on to then beat Richmond in the Grand Final. But luckily for the rest of the competition, Melbourne had also won the 1926 Grand Final against the ‘Pies, ensuring that we didn’t have to hear all about their potential 5-peat for the next hundred years.

And there’s the rub, rivalries aren’t concocted or manufactured overnight, and if they are – then they simply aren’t! True rivalries are built piece by piece and rivet by meticulous rivet, from the ground up, on a traded blow-for-blow basis; they evolve, take emotional shape and are constructed upon their own comparative, and collective accord. Parts equally equal the whole, as the whole more than equals its parts. That Norm Smith grew up following Collingwood, as did Christian Petracca, gives an insight into the personal and at times conflictual nature of playing for a club and being loyal to it, in a sport as traditional, and as time-honoured as ours.

No discussion of a Melbourne-Collingwood rivalry could exclude the ‘upset of the century’, that being the 1958 Grand Final, the unlosable one really, for Melbourne, and the one that would’ve earned us the mantle of winning an eventual 6 flags in a row (from 1955-60). But such is the nature and the brutal meanderings of rivalry; full credit to a young Magpies side who had suffered 9 losses and a draw in their previous 10 encounters with Melbourne leading up to that big dance, a dance they would win by an ‘all-or-nothing’ 18-points.

History shows that Collingwood bashed and crashed their way to defending their 4-peat of premierships that day, but it also created a fire-brand resolve in the Melbourne side that saw it train over the summer months of ’58 and early ’59, for the first time in its history. The Demons of course came storming back to win the next two pennants, but to a player, those two premierships never erased the disappointment of losing the ultimate of battles with destiny itself in 1958. Up to the day Ron Barassi died, he would mention that if he could do just one thing over again – it’d be to play that 1958 Grand Final, and win! He even suggested that at some stage he might get the chance to do so, up in heaven.

When it comes to the greatest individual performance by a player in a red and blue guernsey against Collingwood, it would have to go ‘hands-down’ to our first dual Brownlow Medallist – Ivor Warne-Smith. In the dying stages of the Preliminary Final of 1925, Warne-Smith (who unbeknownst to trainers and officials, had sustained broken ribs the previous week against the Cats) with just 15 players on the field (through injury), he took 9 marks in an 11-minute spell during the dying stages of the match, a match that saw Melbourne soundly defeated, which makes his ‘efforts’ all the more admirable, if not outright extraordinary – that he refused to give in, even when all hope of victory was lost.

The celebrated Frenchman Victor Hugo once said of his beloved Paris, “He who contemplates the depth of Paris is seized with vertigo. Nothing is more fantastic. Nothing is more tragic. Nothing is more sublime.” And when it comes to ‘unpacking’ the Demons – Magpie rivalry it feels very much the same, there is just so much you could touch upon that still wouldn’t suffice for scraping the surface of such an enthralling topic.

That half of Norm Smith’s 10 premierships (as both a player and a coach of Melbourne between the late 1930s to the mid-1960s) came against Collingwood as a direct opponent, goes some way to explaining what ‘part’ this black and white-hued club played in the mind, not to mention the legacy of our game’s greatest ‘coach of the century’. Fittingly, Smith would often respectfully bellow: “You’re not a footballer until you’ve played Collingwood at Victoria Park. If you could hold your head high after a match there…you were a man.”

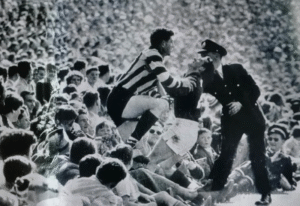

And with that said, my favourite image of this wonderful rivalry, and the above sentiment of Norm Smith’s, is of Ian ‘Tiger’ Ridley in the 1956 Grand Final (a game which saw hundreds, if not thousands stream onto the ground after having stormed the gates to see the two mightiest teams compete for the ultimate prize). But Ridley is literally looking up to the heavens, with his head held high, exhausted – seemingly imploring the gods and himself to get the job done, all while being held aloft by his Collingwood foe, without whom the spirit and pure impetus of competition would not exist.

And so, may these two ‘rival’ teams long have each other in their sights, bringing out the best in themselves, and all that the game means to those of us who revere it.

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter Join our facebook group

Join our facebook group